The African Music Gallery

WASHINGTON—African music is catching hold in the United States. The recent arrest of Fela in Lagos on the eve of his scheduled U.S. tour has captured considerable attention here just as the Kingston shooting of Bob Marley did in 1976 in a newly reggae conscious America. National tours in 1984 by Sonny Okosuns, Tabu Ley and Mbila Bel, Egypt 80 (minus Fela), Sunny Ade, and east coast appearances by Franco and O.K. Jazz have helped to spread the gospel, African style.

WASHINGTON—African music is catching hold in the United States. The recent arrest of Fela in Lagos on the eve of his scheduled U.S. tour has captured considerable attention here just as the Kingston shooting of Bob Marley did in 1976 in a newly reggae conscious America. National tours in 1984 by Sonny Okosuns, Tabu Ley and Mbila Bel, Egypt 80 (minus Fela), Sunny Ade, and east coast appearances by Franco and O.K. Jazz have helped to spread the gospel, African style.

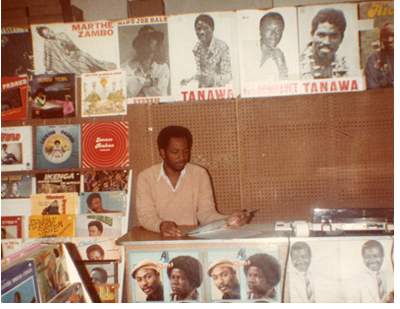

One of the leaders in promoting African music in the U.S. is Ibrahim Bah. At his African Music Gallery in Washington, D.C., Bah imports, retails, and distributes wholesale the latest records African musicians have to offer. Born in the Futa Jalon area of northern Guinea, Ibrahim was raised in Sierra Leone where his family moved shortly after his birth. “I was born into music in a way, not playing music, but the fact that there was always some musical form around you growing up.”

Chief purveyors of popular music at the time were Salia Koroma, the noted Mende accordionist; Ebenezer Calender, playing the maringa style (not to be confused with the merengue of Dr. Nico); S.E. Rogers and his Morningstars; Sami Kamara and the Black Diamonds; the Ticklers; and the Heartbeats featuring the famous Dr. Dynamite. Also of considerable note were the milo musicians, varied ensembles of street players parading up and down with their homemade instruments, beating out incredible rhythms, and drawing crowds wherever they went.

While a student at Sierra Leone Grammar School in the ‘60s, Ibrahim lived in a house on Walker Lane in western Freetown with several older men, each of whom had some connection with music. Through them he got into doing D.J. performances at parties and weddings when the featured bands took their breaks. "If the Heartbeats was there, I was the man around. They would ask me to bring stuff in there and it was such an excitement if they would just let you sit with an amplifier with the speakers and there’s nobody watching you. You’re there by yourself; use the turntable. You’re just filled with excitement just to see yourself operating those little gadgets.”

To make sure they always had the latest records to spin, Ibrahim and his friends would listen to a radio record request program from Brazzaville. When they heard numbers they wanted, they would head for Adenuga’s record shop on Goderich Street or the ABC record shop farther out in eastern Freetown.

Another good source for the latest sounds was the Krootown Road area. “Krootown Road is an area that’s a world in itself. They spearheaded African music in Sierra Leone....lt’s an area where you had just bars. You could walk in one house, have a drink in there, just walk right through the living room to the next house and sit down and get another drink. And the trend then was to get the best African records [to play in the bars]. And it so happened that most of the people that used to live in Krootown Road were seafarers. They used to go to sea and travel from coast to coast and along the way they would bring back these records.”

After completing his education in Freetown, both in school and in the streets and clubs, Bah decided to attend college in the United States. “There was a lot of peer pressure...as soon as you turn around, ‘Hey, he’s gone to the States!’ And when they send back pictures, you know, flashy cars and things, so you tend to think, hey, once you come over here it’s all smooth sailing. So after a few of my friends left I said, ‘Well I can’t survive in this society without at least...going to the States.’ So I saved up money, took a shot at it, and here I am.”

Settling in Washington, D.C. in 1974, Bah soon found his love for African music to be much stronger than his love for school. The music was not fashionable at the time and records were extremely hard to get. Many African students had records that they brought with them from home and Bah would tape them every chance he got. Out of this experience the African Music Gallery was born. “The desire, wanting the records is just what pushed me into it. I didn’t know a thing about the market set up. All I felt was...once you know one guy, maybe there’s a clearinghouse somewhere, you know, you write to these people and....”

He wrote letters and made countless phone calls to London, Paris, and Abidjan but soon learned that the African record business was more complex than he had anticipated. Gradually, through trial and error, he developed the right contacts and began importing records. Operating on a small scale from his apartment, under the name Sahara, he sold to friends and began to build his business through word of mouth. Scarcely more than a year later, he had saved enough money to rent a shop and in November of 1981, the African Music Gallery opened for business.

It hasn’t always been smooth sailing but Bah now feels comfortable with the record business. “I’ve overcome that panic. Now what I’m working at is trying to establish the music here, trying to have it accepted and also getting into production.” First productions for the African Music Gallery label will be the albums Manuela and Samedi Soir by Bopol Mansiamina the popular young bassist from Zaire. Previously available only as imports, these two albums mark the beginning of a planned series of U.S. releases for 1985. Bah eventually hopes to attract African musicians to America to do the actual recording of their music. By pressing records here, instead of importing them, he hopes to be able to reduce prices and thereby make the records more marketable.

Another aspect of marketing the music is Bah’s involvement in promoting live concerts by African bands. He successfully arranged Franco’s 1984 appearances in New York and Washington and hopes to bring Les Quatre Etoiles (Bopol, Nyboma, Syran, and Wuta Mayi) over for a national tour in April or May with Afro National to follow sometime later.

Concert promotion, like the rest of the music business, is not without its pitfalls. Bah tells the story of his recent experience with Franco and O.K. Jazz. “I spoke with Franco several times and we had agreed we were going to have twenty-five people in the group...and I applied for the visas and got the visas. A week or so later he got pressure from his quarters that some people must be in the band, and he called me and said, ‘Look Ibrahim, I cannot come with just twenty-five, I’ve got to come with forty-five people.’ I said, ‘You mean forty-five, four, five?’ He said, ‘Yes, forty-five.’...He gave me the additional names, and I applied [for visas] for the rest of their names. And immigration said, ‘Hey, one moment this group is twenty-five, the next minute they’re forty-five; what kind of group is this?’” In the end, the visas were issued and the tour went ahead, but Bah was somewhat chastened by the affair.

Despite the peculiarities of the business, he sees a bright future for African music in the U.S. “Once the people can hear it...they can appreciate it. A lot of people may give you an excuse, ‘Oh I do not understand what they say; I don’t understand what they are talking about.’ These same people go out and listen to instrumental music! They don’t complain that they don’t hear the guy singing!”

With his shop, a newly published mail order catalog, record production, and concert promotion, Ibrahim Bah seems destined to be at the forefront of the African music invasion of America. “I can’t think of any better business to be in than the record business. Not just for the money, but for the pleasure of listening to African music and being with friends and customers who drop in to talk and learn more about the music. I get a lot of pleasure from that.”

This article first appeared in West Africa, no. 3564, 16 December 1985. Copyright © 1985 by Gary Stewart