The Life and Death of S.E. Rogie

LONDON—It’s hard to imagine a world without S.E. Rogie. Having worked with and written about Sierra Leone’s affable singer-guitarist from time to time over the last ten years, his presence—although lately sporadic and a good distance across the Atlantic—seemed to me to be one of life’s few reliable constants. Despite the warning signs of high blood pressure and last spring’s open heart surgery, the sixty-something Rogie appeared fit enough to sail smoothly into old age like a cup of palm wine on the palate at the end of a hard day.

But that’s not the way it happened. Rogie died in London on the 4th of July [1994] from the combined effects of a stroke and heart attack suffered in Estonia nine days earlier following his performance during a WOMAD festival. Death came amidst the second flowering of a career that had seen its first bloom in West Africa in the fifties and sixties, a decade and a half of near dormancy in the United States, and a move to London in 1988 where a wealth of concert dates and recording contracts brought him his current celebrity.

S was for Sooliman, E for Ernest, and Rogie a nickname for Rogers, a family name that came to Sierra Leone in the days of slavery and the repatriation movement that brought freed slaves home to colonies in West Africa. Rogie was born in the 1920s—he never knew the exact date—among the Mende people in southern Sierra Leone. Always self-motivated and largely self-taught, he left his parents at an early age and moved to Freetown where he learned typing, tailoring, and ultimately music. By the mid-fifties he was an accomplished enough musician to record songs at Freetown’s best known studio, Adenuga & Jonathan. Using earnings from those first sides and the help of a wealthy patron, he purchased recording equipment for himself and launched his own Rogie and Rogiphone labels.

With his wonderfully mellifluous baritone and folksy palm wine guitar, Rogie, backed by a couple of pick-up percussion players, cut a series of records that carried him to his first peak of renown. His most famous song, “My Lovely Elizabeth,” based on his own broken romance, moved him into the international arena in 1962 when EMI picked it up for worldwide distribution. Around 1965 he added electric guitars to his acoustic sound and formed a band called the Morningstars with which he recorded some of his best material including “Baby Lef Marah” and “Man Stupid Being.”

By his own admission, however, he squandered the fruits of stardom. His indulgence in easy ladies and abundant booze consumed cash faster than it flowed. By the end of the sixties Rogie found himself shoulder-deep in personal crisis. He gave credit to a spiritual awakening for the renewed sense of self and purpose that pulled him from his depression.

Rogie left Sierra Leone for the United States in 1973 and settled in the San Francisco Bay area, where his gentle palm wine music crashed head-on into the barriers of America’s Top-40 mind-set. Despite several new recordings and years of live performances, he never rose beyond the level of local cult figure. His most enduring contribution of the period took the form of an African cultural program of music, lecture, and slides that he presented to adults and school children in the Bay Area. Not until 1986 when he released an album of his 1960s hits did a wider audience again beckon.

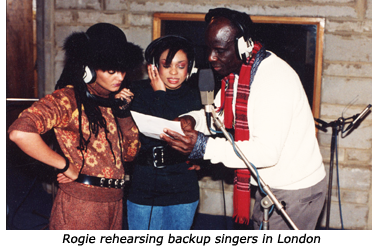

Copies of The 60s’ Sounds of S.E. Rogie sent to London fell into the hands of BBC disc jockey Andy Kershaw who couldn’t keep them off his turntables. The Kershaw connection led to a record deal with London’s Cooking Vinyl and a promotional tour of the U.K. These successes convinced Rogie to stay in England where his career once again took off. More recordings for the Workers Playtime label and tours with the WOMAD festival followed. He concentrated on performing rather than writing in this later period, recycling his old hits with new arrangements and sometimes altered lyrics and titles for the new generations who became his fans.

Smooth and urbane on the outside, Rogie charmed his audiences with a grandfatherly folksiness and delightful repertoire of stories and songs. Prickly and temperamental with intimates, he insisted that colleagues meet his high standards of musicianship and professionalism. A humanitarian at heart, he could appear naive and world-wise almost in the same moment. He wondered at the world’s random goodness and cursed its wanton inequities. He rued his long absence from Sierra Leone and longed for the renewed adulation of his countrymen. Rogie finally exorcised this latter demon over last New Year’s holiday with a triumphal round of concerts in Freetown to benefit refugees from the fighting in Liberia and southern Sierra Leone.

Back in London Rogie underwent a lengthy heart bypass operation in February and seemed to be making a full recovery. He completed work on Dead Men Don’t Smoke Marijuana, a new compact disc for the Real World label, his most prestigious recording deal since EMI in the early sixties. In June he returned to the WOMAD tour playing dates in Germany and eastern Europe, where he was stricken on June 25. He was flown to London for treatment but reportedly never regained consciousness. A memorial service for Rogie was held in London and his body flown home to Sierra Leone for burial. Survivors include his wife Cecilia and three children; daughters Messie and Yatta; and son Brima, a Los Angeles-based musician who plays under the name Rogee Rogers.

Rogie neatly described the nature of his music and philosophy in an interview with Sarah Coxson of Folk Roots several years ago: “The essence of Palm Wine music is to pass on your experience to other people for their betterment....If you’ve made some mistakes or done some good things in your life that could be exemplary, I pick out the important part and put it into song for other people to learn from that. That’s the kind of thing I like to see. The only thing in the world that can bring peace to the world is the sharing of experience and love. All the good things that I want for myself, I must wish for others to have the same things. When I try to monopolise that thing there is no harmony there. I cannot be at peace while I see all my brothers and sisters suffering.” If Rogie is still in touch with the world that he’s left, his feelings for our condition will not have changed.

Dead Men Don’t Smoke Marijuana by S.E. Rogie on the Real World label is distributed in the U.S. by Caroline Records, 114 West 26th Street, New York, NY 10001.

This article first appeared in The Beat, vol. 13, no. 5, 1994. Copyright © 1994 by Gary Stewart