Soul on Fire

WASHINGTON, D.C.—“Play I on the R and B, want all my people to see,” cried Bob Marley in 1976, appealing to America’s radio programmers to air his music. But Marley’s plea fell on deaf ears. Today, more than a decade later, most of the world’s musicians continue to struggle behind a tinsel curtain of cultural apartheid.

In the United States, the world’s largest entertainment market, radio air play is the key to success. Music that fails to conform to a homogenized, top forty formula is usually ignored by high powered commercial stations, and is relegated instead to low power, small audience alternative radio. The major record companies, whose wealth affords them the power of promotion, are co-conspirators.

Despite the odds, an occasional breakthrough does occur. Harry Belafonte engineered the fifties’ calypso craze. Jamaican singer Millie Small scored in the sixties with “My Boy Lollipop.” Bob Marley himself was on the verge of breaking through before his tragic death in 1981.

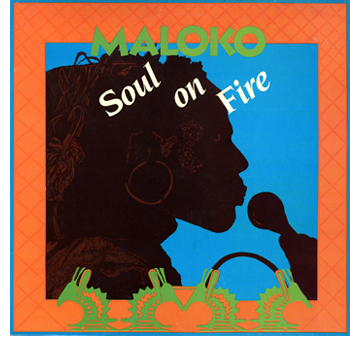

The next musician to break the top forty strangle hold will be an African—at least that is the intention of Sierra Leonean record producer Ibrahim Bah. From his Washington based African Music Gallery—a retail, distribution, and production company—Bah works for the day when African music will capture America’s attention. Soul On Fire, his current attempt to smooth the road for such an occurrence, is the fusion of old soul standards, songs familiar to most Americans, with the sizzle of Congo music. “The problem,” he says, “is to get Americans to listen to the music of the rest of the world. We need to crack the door open.”

Cameroonian guitarist Vincent Nguini was Bah’s first recruit for the project. Nguini grew up in Yaoundé listening to American jazz guitarist Wes Montgomery on the radio and imitating the sounds on an old guitar strung with fishing line. He came to Washington after extended stops in Abidjan, Accra, Geneva, and Paris where he refined his craft with various bands, including a stint with Manu Dibango. He and Bah narrowed the list of songs for the new album, and Nguini set about arranging the music. A James Brown number, “Cold Sweat,” Ben E. King’s “Stand By Me,” “Direct Me” by Otis Redding, and Wilson Pickett’s “In The Midnight Hour” are among the seven classics selected. “I used to listen to the songs as a boy,” Nguini says. “The rhythm is already a dance beat. It is easy to play but difficult to arrange in African style. You don’t know how African people are going to take it, because it was Americanized. At the same time Americans would find it different from how they are used to hearing the songs.”

Nguini’s steady guitar, bass, and keyboard work anchors an illustrious ensemble that he calls Maloko (Douala for pleasure or enjoyment). Zaireans Syran Mbenza and Jean Papi, who were in the U.S. performing with the Four Stars, joined in the recording session. Syran’s soaring guitar and Papi’s smooth vocals do battle with the punchy, soulful voice of American rhythm and blues singer Tommy Lepson in a Matonge (Kinshasa’s quartier d’ambiance) meets Motown duel.

Ghana’s Okyeremah Asante, now resident in the U.S. following his work on Paul Simon’s Graceland tour, contributes percussion chops. On drums is another member of the Four Stars tour, Komba Bellow of Zaire. Trumpet player Tete Fredo of Cameroon, whose stellar session work helped make Paris the place to record African music in the late seventies and early eighties, leads the rousing horn section.

For Lepson, a white singer who was voted the Washington area’s best male rhythm and blues singer in 1987, it was his first encounter with African music. “I thought it’d be cool. I thought it’d be a challenge,” he says of the project. “I first asked Ibrahim if he didn’t want a black man, but he said no that the voice was most important.” Bah and Nguini coached him through the complicated arrangement that sometimes called for a double chorus or only half a verse. “I just had to wing it,” he says.

Bah anticipates some criticism from purists on both ends of the musical spectrum. “I don’t think music is a matter of philosophy,” he says. “It’s a matter of entertainment. The old music we copied has proven it’s good. The African music we have is good. When you put two good things together, how can you get bad? I don’t think we’re bastardizing the music at all. What we’re doing with Maloko is opening up the doors. People will ask questions and the answers will lead to African music.”

Initial response from the industry and public has been positive. RAS Records in the U.S. and Stern’s in England have agreed to act as distributors for the record. Several major radio stations have given it an airing, and the music press, including Billboard and Rolling Stone, have promised to do stories. But no matter how his gamble—and it has been considerable—turns out, Bah is philosophical. “For me, music is fun,” he says. “I can take the good with the bitter. For me to come up with this concept is benefit enough. Life will go on after Maloko, but I look forward to it doing well.”

This article first appeared in West Africa, no. 3722, 12 December 1988. Copyright © 1988 by Gary Stewart