Ubongo Man Has Come

Remmy Ongala

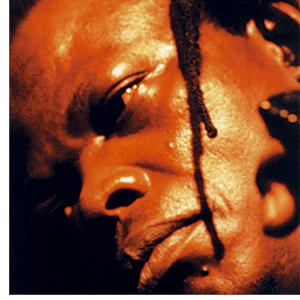

TORONTO—At times Remmy Ongala looks like a wild man, his bare chest draped with strings of cowries and assorted amulets, his lower body swathed in brightly colored cloth. A wig of teased grass crowns the carefully braided locks which fall haphazardly about his head. On other occasions he’s a Tonton Macoute, sinister, menacing, dreadlocks hidden under a wide brim, flat top hat, his eyes staking out the crowd from the cover of dark glasses. A T-shirt and khaki trousers mold themselves to his well-rounded frame; a guitar rides his protruding belly like a high strung AK—47.

Ongala’s looks are striking, but it is his music that commands serious attention. He sometimes strolls on stage alone at the beginning of a show, plucking his guitar while introducing the members of his Orchestre Super Matimila as one by one they take the stage to pick up the beat. When the band hits full stride, Ongala begins to sing with a surprising sweetness and clarity. His words, usually in Swahili, ride the repeating guitar riffs, melodious and intense. In a voice that sounds strikingly like Madilu System of O.K. Jazz, Ongala delivers a lyric as if he owns the words. Whether or not you understand his message, this is clearly a man of passion.

His music is a throwback to the late sixties and early seventies, a rootsy blend of Congo music and the rhythms of East Africa. Listen to Original Music’s wonderful oldies collection The Tanzania Sound—especially Salim Abdullah with the Cuban Marimba Band, Hodi Boys, and National Jazz Band—and some early Franco—perhaps l’Afrique Danae No. 6 from Sono Disc which still occasionally pops up in African record bins—and you’ll hear where Remmy Ongala and Orchestre Super Matimila are coming from. It’s a stripped down sound, lean and agile, no drum machines or synthesizers or redundant players clogging and suffocating the music—a space for everyone and everyone in his space.

Sounding hauntingly like Franco, Ongala plucks his guitar blending seamlessly with a second lead and accompanying rhythm guitar. Kick drum and congas carry on for a generally absent bass while driving the music in a kind of slowed down benga beat. A muted cymbal cracks in double time much as the maracas did two or three decades ago. And a saxophone, the Congolese guitar’s most complementary consort, backs and fills and solos.

Ongala calls his music “ubongo,” the Swahili word for brain, because it is “music of the brain; it’s heavy thinking music.” Since he sings in Swahili, most westerners must content themselves with the lilting musical quality of his voice. But it helps to know that the words which nip sweetly at our ears have a keen and powerful bite when their meaning is understood. “I sing about things everyone should have in life that will give us all a certain equality,” he says. “As for me and my songs, I always go to the world. The world is a prison, because there are also people who are proud of their lives and others who are always suffering....I’ve seen people who had a lot of money and they’re all dead. They leave everything here on the earth. Many musicians sing about love, about life. It’s always like that. And they don’t sing about something that’s going to make people [better], [about] what needs to be done to this world. So I try not to sing very much of love, [but] to try to illuminate the situation of the world.”

At the time of his birth in 1947, poverty and inequality were wanton in the old Belgian Congo (now Zaire), one of the most severe and exploitative of Europe’s African colonies. Ongala’s family lived in the eastern part of the country at Kindu, 200 or so miles west of Lake Tanganyika and the borders of Burundi and Tanzania (although he has also claimed Kisangani some 250 miles to the north). His beginnings, as he tells it, were extraordinary, a marathon of sorts, both distressing and magical.

Like thousands of other African men who fought for their colonial occupiers during World War II, Ongala’s father returned home at war’s end, married, and settled back into the life of his country. His wife became pregnant, but the child died. A second pregnancy again ended tragically. In despair his mother went one day to see a local traditional doctor. “So the doctor said it was the same child who arrives each time,” Ongala relates. “So he said to my mother, ‘The next time you are pregnant you mustn’t go to a hospital. Come to talk to me, and I’ll explain how to have the child.’”

When time came for her to give birth, she followed the traditional doctor’s instructions and delivered the baby, who turned out to be Ongala, in the forest with the doctor in attendance. “I was born feet first with two front teeth.To us, there is a special significance when you are born with two teeth." It is, he explains, almost like an inheritance; one born in such circumstances can become a traditional doctor if he chooses. He was named Ramadhani Ongala Mtoro, and later when he decided to become a musician, he adopted the title “doctor” in remembrance of his auspicious birth.

The doctor warned Ongala’s mother never to cut his hair, an admonition she rigidly followed for fear of losing her thrice-born child. His shaggy locks were a source of shame and ridicule, but his mother remained steadfast. Only once, on her death, did Ongala take a razor to his head. Later, he says with a laugh, “When records by Bob Marley came out, I saw that he had hair like mine. So after that I felt all right. I became proud of my looks.”

Music is an integral part of life in Africa; it accompanies the routine as well as the ritual. From the moment of birth Ongala was immersed in it. As a young boy, he quickly learned to play hand drums from his father who was a traditional singer and drummer. As a teenager in the early sixties, he taught himself to play guitar. The new urban Congo music style was flourishing during his youth. Radio and records brought the sounds of Kinshasa and the rest of the world to even the most remote villages. Ongala loved listening to Cuban records—strange yet familiar African rhythms returning home from across the Atlantic. From Kinshasa rang the golden voice of Joseph Kabasele and the mellow rumba guitar of Franco. These, Ongala fondly recalls, were his primary musical influences.

As his Franco-like guitar picking improved, he began to play professionally getting gigs with assorted African pop groups at local hotels in eastern Zaire. His big break came in 1978 when an uncle living in the Tanzanian capital of Dar es Salaam sent for him to come join an ascendant band called Orchestre Makassy. He left Makassy after nearly three years to join Orchestre Matimila, a new band he soon made his own.

In the sixties and early seventies Tanzania, as did most of the rest of Africa, succumbed to the powerful influence of Congo music. But in the mid to late seventies, as the once prosperous East African Community disintegrated and Tanzania chose to follow the development prescriptions of its charismatic President Julius Nyerere in increasing isolation, the music scene in Dar es Salaam was transformed.

As the country began to look inward, President Nyerere set up a Ministry of National Youth and Culture to foster local styles of music and dance. But failed development experiments, the shock of rising world oil prices, declining prices for Tanzanian exports, and war with neighboring Uganda, which led to the ouster of the notorious Idi Amin, plunged the Tanzanian economy into decline. Precious foreign currency necessary to finance imports, including musical instruments and recording equipment, began to dry up. A record pressing plant planned in the sixties has yet to be set up, although much of the equipment was purchased in the seventies. The Tanzanian Film Company, which is responsible for the country’s recording industry, could barely maintain a rudimentary two track recording studio.*

The result has been a largely isolated, but self-contained and even flourishing local music industry. Radio Tanzania, unable to acquire foreign exchange to purchase imported records, began to stock a tape library of music it recorded with local bands. Live music replaced disco in many urban clubs. Today in Dar es Salaam Ongala estimates there are at least twenty bands playing every night. It is within this atmosphere that Orchestre Super Matimila developed.

The band got its name from a small village of a friend of Ongala’s and its equipment from a local businessman with enough connections to navigate the country’s import laws. They played live shows, as many as five a week, and began to record some of their best songs for Radio Tanzania. In addition to gaining valuable radio air play, the tapes were often sent to neighboring Kenya for pressing into records, which in turn spread the band’s reputation beyond Tanzania’s borders.

But increasing fame failed to yield increasing fortune “There is no copyright. There are no unions. I’m just beginning to sort that out,” Ongala complains. “You send your tape to Kenya to make records, 2000 records. He says to you, ‘I’ll put 1000 out,’ when in fact he’s put 2000 out What can you do?”

What Ongala did was to give one of his tapes to an English friend who was returning to London after visiting Dar es Salaam. The friend passed the tape on, and it found its way to WOMAD (World of Music, Arts and Dance). From that chance introduction, Ongala and his band were invited to join the 1988 WOMAD tour, during which they performed to wide critical acclaim. At the same time, the WOMAD record label issued an album of some of the group’s best radio tapes from the early eighties.

The LP, called Nalilia Mwana is probably Ongala’s finest work (liner notes refer to “inferior” sound quality, but that is an unfortunate exaggeration). It offers songs like “Sika Ya Kufa” about the death of a fellow musician, “Ndumila Kuwili” don’t speak with two mouths, and “Mnyonge Hana Haki” the poor have no rights. “I think all time for the poor, like ‘Sauti Ya Mnyonge,’” he says citing a song that translates as the voice of the poor or underdog from an earlier LP, On Stage With Remmy Ongala.

On record he uses more vocal harmony than in live performance. A second lead and backing vocals appear on several songs. Harmonizing saxophones and even trumpets show up on others. But the sound of Ongala insistently spitting out his message over rolling, repeating, equally-insistent guitars dominates the music.

Rave notices for his work with WOMAD led to the group’s inclusion in the 1989 WOMAD tour and a brand new album, Songs for the Poor Man, on WOMAD affiliated Real World Records. Recorded in England at the Real World Studios, Songs for the Poor Man is Super Matimila’s first work in a modern western studio. As always the messages are strong and passionate, a remake of “Sauti Ya Mnyonge,” “Karola” which says “be careful in a world where you believe there is goodness,” and the anti-racist “Kipenda Roho.”

Next to the anguish of poverty, the evil of racism is close to Ongala’s heart. He is married to a white Englishwoman with whom he has three children. “In the world now, it’s a new world,” he reasons. “We don’t have the old world that we had....My children, they’re not white and they’re not black, they’re children. We come from the same father. We’re different, but we come from the same place....My children are the children of the whole world. My children are everyone’s children. They’re not white; they’re not black. I can’t work with that [racist] system.” He sings about it in "Kipenda Roho:”

What the heart loves

The body follows.

Love has no colour

Love has no race.

And how is his message being received in the West? “Why shouldn’t it be accepted?” is his retort. Why not indeed? After all it is music for the brain and for the feet and hips as well. If acceptance is not yet total, at least this dreadlocked, consciousness raising African is beginning to get a hearing.

* For an excellent look at the recording industry in small countries including Tanzania, see Big Sounds From Small Peoples by Roger Wallis and Krister Malm, London: Constable, 1984.

This article first appeared in The Beat, vol. 9, no. 2, 1990. Copyright © 1990 by Gary Stewart